My father-in-law passed away last week. It was expected, but still came a bit sooner than we were ready for. We had just brought in hospice the day before and we were working to get him settled and comfortable. Tuesday just before midnight, my husband, Allen, got the call. I came into the kitchen and held him as he sobbed. “I just saw him today. I wasn’t ready for this,” he said. I soothed his hair and said, “I know,” over and over again.

My father-in-law passed away last week. It was expected, but still came a bit sooner than we were ready for. We had just brought in hospice the day before and we were working to get him settled and comfortable. Tuesday just before midnight, my husband, Allen, got the call. I came into the kitchen and held him as he sobbed. “I just saw him today. I wasn’t ready for this,” he said. I soothed his hair and said, “I know,” over and over again.

I’ve been there. But it was my there, and not his there. And no two “theres” are the same.

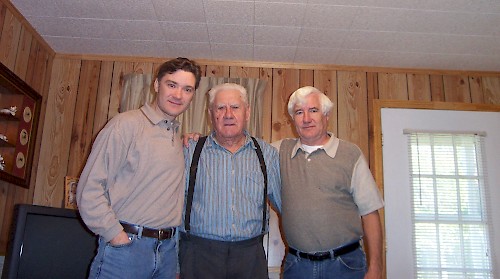

His dad, Allen Franklin Raines (he and my husband share a name), was The Patriarch and undisputed leader of the family. He was an old-school provider, and he moved the family all over the south for most of my husband’s childhood. He worked his way up from nothing (and I mean, nothing) to lead teams of engineers building Procter & Gamble plants. It was only in the last few weeks of his life, when his condition got really bad, that any of the children (my husband has one brother and one sister) felt comfortable making any decisions. Many of those decisions fell to my husband, because he is the oldest. He is also a man who does not like to make big decisions, handle emotional messes, and deal with details. He did all of these things though—often with my gentle nudging—and he did them remarkably well.

There was one more nudge I had to give my husband, involving writing and delivering a eulogy for his father. He wanted to, but he was afraid of breaking down. I told him the same thing I tell myself and we tell our two children: Fear is usually not enough of a reason to avoid doing something necessary or good. “Besides,” I told him, “I have your back on this. I’ll step in if you need me.”

Pushing a person who has just lost their dad seems kind of mean, I know. But I see it as a kindness. My husband is one of the most capable people I know. He might be the most capable. Yet he constantly underestimates himself. I wasn’t letting him talk himself out of something I knew he could do. When my father passed away five years ago, writing and delivering his eulogy was such a healing experience, and I wanted that for my husband, too.

For two days, he worked on the eulogy. His first draft spilled out easily, and then he edited and refined every word. He read it aloud with each draft, breaking down in different sections each time. “Just breathe,” I would whisper when he did.

He decided to focus on how different his father had been from his grandfather. My husband’s grandfather was generally not a good father or husband. He didn’t exactly leave the family, but he sure didn’t lead them. By contrast, my husband’s father took his role very seriously—avoiding the demons that claimed so many of his family members in Mississippi. (There was a reason he didn’t stay.) As I listened to my husband practice, it struck me as interesting that he had focused on how different his father and grandfather were from each other—because he was also so different from his own father.

My father-in-law was driven by ambition and duty, and I think he consciously set out to be different from his father, because of what he saw lacking. My husband never felt that lack, because his own father was solid, dependable, and present.

That doesn’t mean my husband didn’t set out to be different, too.

For one, he’s no Patriarch. And I’m no Matriarch. We’re people. Parents. Equals. We’re a family, but we lead together. I didn’t change my last name, and we bucked pretty much every convention after that. We structured our partnership quite differently than his parents did. My husband was a stay-at-home dad for eight years, until he started working part-time from home last year. I’ve always been the breadwinner. He’s always done most of the household tasks. We rely on each other, but in very different ways than his parents relied on each other.

Also, my husband is silly with our kids. And he’s vulnerable with them. He tells them constantly that he loves them. He knew his dad loved him, but these weren’t things fathers said or did in his dad’s generation.

It took my father-in-law a long time to understand that his son was doing it differently, and that my name wasn’t, in fact, Judi Raines. He got it in the end though, and he would talk to me—as an equal—about ambition and the importance of providing for the family. He’d see me exhausted, and he would say with his Mississippi draw, “Judi, how you doin’ girl?”

As my husband gave the eulogy at the funeral Saturday morning—often with a shaky voice, but so beautifully—I knew his dad would have been proud to see that his son made his own decisions. That’s what it all is, isn’t it? You’re born into a generation, and you either look at what has come before and repeat it, or you tweak it.

The Raines men are tweakers, and that is the harder path. It’s also the only path that leads you to what’s next. It’s no coincidence that I chose this family to marry into.

As for my husband, he was so glad that he gave the eulogy. “It helped me work through so much,” he said. I think it helped every single person at the funeral, to be honest. Definitely me and definitely our children.

Rest in peace, Allen, Sr. You will be missed at every turn. Thanks for opening up the path.