I’ve always been kind of an outlier. Not demographically or in a way that is apparent to others. After all, I’m a middle-aged, middle-income, brown-haired, blue-eyed white girl, who lives in a quiet suburban neighborhood in Ohio and follows a routine you could set your watch by. Hello, vanilla.

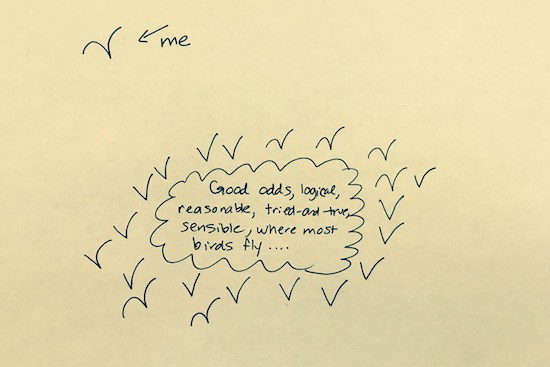

It’s the psychographics where I push the limits—as in, my attitude, beliefs, and choices. I’ve always had a fixation with wedging myself into those slim spaces a great majority of people either don’t bother with or think aren’t viable opportunities. Where others see probably not, I see hmm,that could be something.

My career choice to be a freelance writer is the most obvious manifestation of this. The more people who told me going freelance seemed like a risky move—one fraught with uncertainty and instability, with a myriad of headaches to deal with, like taxes, health insurance, and unsteady cash flow—the more it seemed like a really great idea to me. The first conversation I had with my now-husband (back then, just a Match.com connection) happened to be the week I was making the decision to be a freelance writer. He tried to talk me out of it.

I knew I had to marry him.

(Actually, that is completely untrue, but just sounded so good! I didn’t even like him. He grew on me slowly, and five up-and-down years later, we got married.)

Anyway, the point is: all of those people were wrong and I’ve been thriving as a freelancer for 15 years—including supporting that naysaying husband and our two kids! (Taxes, health insurance, and unsteady cash flow are a major pain in the ass though—that much is true.) For a long time, I thought it was all about this complex I have about proving people wrong. Like it was my jam to subvert expectations. Ego shows up in all different ways. Some people brag. Some people commandeer conversations. Some people live alternate lives on Facebook. Mine shows up as quietly proving you dead wrong. You don’t even have to know I’ve proven you wrong. I just want the satisfaction for myself. (Though I’ll probably write about it and casually send you the link.)

But the older I get, I see that this desire of mine to be the asterisk on the list is more than just ego. It’s legitimately the way I perceive opportunity.

For example, as an essay writer, I write and pitch a lot of essays. I get about half of them published. Some of my favorite ones are the pieces that got a “yes” from publications that don’t normally publish the kind of piece I sold them. More than one editor has told me that the piece of mine they are publishing is an outlier. Now, I can write a good essay—but so can many writers! The difference between them and me is that dissuasion doesn’t tend to deter me that much.

In the weekly market guides I get from Freelance Success (a fantastic writers’ forum I belong to), I’m always on the hunt for the slim window, where the editor or content manager interviewed says something like, “We occasionally buy such and such a piece.” Occasionally is my trigger word. An op-ed market guide like this is exactly what led me to pitch The LA Timesthis funny essay about how my dad hated Ronald Reagan. Slice-of-life, humor pieces are not the kind of pieces they typically publish in their op-eds. But when the editor made a point to say she sometimes buys them, I couldn’t pass up the chance to test that “sometimes.”

To be fair, being an outlier involves just as much rejection as any other approach. I get told “no”—or worse, ignored!—on a weekly basis by any number of publications or potential clients. Various versions of that Ronald Reagan essay got rejected by six or seven different outlets before I retooled it for The LA Times. And though I’ve written several essays for the New York Times, I’ve yet to score a byline in the much-coveted Modern Love column. Not only that, my agent and I are trying to sell my young adult novel, and the process is brutal.

Rejection is just part of it, no matter what—so why not assume the odds may be in your favor? I am reminded of a scene in Dumb and Dumber. Jim Carrey is talking to the girl he wants to win, asking her what his chances are. She says, “One out of a million,” and after a pause, he says, exuberantly, “So, you’re telling me there’s a chance!”

It’s not dumb to try. In fact, it’s become a way of life for me, the suburban vanilla girl with a big asterisk next to her name.