I write a bimonthly column for Cincinnati magazine, where I focus on the experience of midlife. Usually, I write about whatever is going on in my life or happening in the world (or my city) at that moment.

In June of 2020, I wanted to talk about racism, because to write about anything else felt trivial. At the same time, as a white person, I understood that no matter how much I reflected on the ways in which I’d participated in racism in my life (the gist of my essay), my writing would still have problems and could ultimately cause harm to Black readers.

I knew that good intentions could be just as damaging as bad ones. I started to write, not at all sure how I would mitigate this, but knowing it was my responsibility to figure it out.

As I was finishing the piece, I happened to see the post of a white colleague on a journalism Facebook group I belong to. She linked to a story she’d just had published related to the Black Lives Matter protests. I saw that Kelly Glass, whose byline I recognized, had left a comment asking if the writer had considered using a sensitivity reader for the piece. I knew that fiction writers often used sensitivity readers, but seeing Glass’s comment was the first time it occurred to me that a journalist could hire a sensitivity reader, too.

So I finished my essay, and hired Glass, who is Black, to do a sensitivity read. For $45, and within two days, she read a draft of my piece.

She didn’t make any edits. Rather, she offered specific in-line comments. Some comments were suggestions to change a word. Other comments encouraged me to reflect on how I was presenting a situation, with suggestions for language I could use to reframe it (if I chose to).

For example, I wrote:

“Whereas Black people experience racism in their daily lives, white people just have flashes of recognition about racism.”

She suggested that I mention the different types of racism Black people deal with (she offered an explanation of what those types were) and clearly state what I meant by flashes of recognition (she offered questions for me to think about).

I wound up editing the sentence to:

“Black people experience racism both as specific incidents in their daily lives, as well as cumulatively, as one generation inherits the effects of racism from the previous one. But white people merely have flashes of recognition about racism, whether it’s a moment of recognizing racism within themselves or, more commonly, within others or an institution.”

In another place, I described my memory of a Black female student getting shut down in a college history class. I wrapped up the section talking about how I felt about the exchange. Glass encouraged me to circle back and reflect instead on how that young Black woman must have felt. I had also talked about my shame over realizing my role in racism. “Mentioning your shame potentially centers your own negative feelings. Avoid this,” she wrote.

I’ve worked to educate myself about how white people center ourselves, and I even knew that. But it slipped into my writing nonetheless.

Overall, her reading of my piece was incredibly thoughtful and helpful, and I can’t overstate how grateful I feel to have worked with Glass. You can read the final piece here.

What Is a Sensitivity Reader?

Glass was gracious enough to chat with me about how journalists can use sensitivity readers. I also talked to two other sensitivity readers. The first thing I realized is that the name “sensitivity reader” is really in the way of describing what they do.

A “sensitivity fact-check” could be a better way to think about what she does, Glass says. “Even amongst those of us who do sensitivity reads, there is talk about whether the term sensitivity reader accurately captures what we do.”

Glass defines a sensitivity reader as someone who has a lived experience as a marginalized person, the relevant historical and cultural knowledge of that experience, and the editorial experience to read manuscripts and articles with representation in mind.

She will often read a story a non-Black journalist has written about Black issues, and come away feeling like something is missing. “When you are writing about Black issues and you don’t have that lived experience, it is very easy to miss things and to misrepresent a community,” she says.

“The most common misconception we encounter is the notion that the purpose of sensitivity readers is to ‘sanitize’ writing so that it's more politically correct and doesn't hurt anyone’s feelings,” says Kim Vanderhorst, who runs the sensitivity reading department at Salt & Sage Books.

“It would be more accurate to call us ‘Authenticity Readers’ or ‘Cultural Consultants’ or something to that effect,” she says, emphasizing that it’s not about avoiding hurt feelings. Rather, it’s about accuracy. “Tokenism and harmful stereotypes pervade all manner of print and digital media, and having someone with an experienced viewpoint review materials with a view towards making them more inclusive and accessible can be beneficial to publications and corporations alike,” Vanderhorst says.

Jenna Beacom, who has worked as a sensitivity reader for pieces that deal with representation of the deaf community (she is deaf) has noticed sensitivity readers being demonized as part of “cancel culture,” especially on Twitter. “This all ascribes way more power to us than we really have. We make recommendations, with the intent of making your piece stronger. These recommendations are just recommendations! You may take them or leave them!” Beacom says.

When to Use a Sensitivity Reader for Your Story

Many journalists are still hesitant to engage a sensitivity reader. “For a journalist to admit that they need a sensitivity reader could be to admit that another journalist could do a better job,” Glass says. That’s not the case at all though. She encourages journalists to think of using a sensitivity reader the same way they think of using a “tip.” It’s an opportunity to write an even stronger story.

“My recommendation is that every journalist writing about deaf-related issues consult with a sensitivity reader at least once. It's very likely that a single consultation will go a long way, as there are many principles that can be raised by a given article, but then be applied broadly.” Beacom says. Things like noticing who is being centered — the deaf person or hearing people around that person? Or avoiding what’s often called "inspiration porn," where a hearing audience is meant to be uplifted by a deaf person's brave struggle (that applies to many other disabilities, too).

Also, it’s important to note that working with a sensitivity reader can be about more than catching word choice and style, like Black versus African American, or whether deaf should be capitalized. It’s often about the thrust of the whole story.

“Journalists can miss entire stories altogether by not being tuned into the community they are reporting on,” Glass says. That’s true of any marginalized community, whether the marginalization is related to race, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, class, mental or physical disability, or a mental health condition.

Engaging a sensitivity reader earlier in the process can be very beneficial. “You can say to the sensitivity reader, ‘This is what I’ve got and what I plan to report.’ And because they have that lived experience, they can maybe point out other options, like another way you might want to go with the story, but not in a way that oversteps the story,” Glass says.

For example, I wrote an essay for The New York Times a few years ago called, “Can We Ever Truly be Fearless?” I was looking at the cliché of “being fearless” and how this idea bothers me. I interviewed experts who study fear. I mentioned PTSD briefly because one of my fear experts talked about the fact that a certain percentage of people develop it after experiencing fear or trauma. One of the commenters on my piece said, “This is incredibly stigmatizing and in the most harmful possible way,” and at least one person agreed (there were a few other comments that suggested I minimized the discussion, too). At the time, I thought, No, they just didn’t get what I was saying or what I meant and that’s not *really* what the piece was even about.

But now I look back and wish I had someone with personal PTSD experience to review what I was writing, not so much because I think any particular word I used was wrong, but because it’s possible I missed a whole part of the story.

How Journalists and Other Content Creators Can Find Sensitivity Readers

Though I only have the one experience, and it was with a personal essay versus a reported piece, I found the process to be straightforward. Here are some people to contact:

- Salt & Sage, which Kim Vanderhorst describes as providing “quality editing with kindness,” has updated their rates for 2022. If you’re interested in learning more, fill out this “request a consult” form. You can also read their FAQs or email at hello@saltandsagebooks.com.

- Jenna Beacom says that her rates are a bit below the median rates shown here. For shorter pieces, like children's books or news articles, her rates are usually in the $150 - $250 range, depending on several factors. You can contact her using her contact form on her site.

- Kelly Glass charged me $45 to read a piece under 5,000 words (I paid her via PayPal). She’s now an editor at Parents, and I don’t think offers sensitivity reading anymore (you can inquire by email to check).

- There is a Binders Full of Sensitivity Readers group on Facebook (it’s open to join). The group’s admin created this Google form that people who are not members of the group can use to request a sensitivity read.

- Though it doesn’t offer a specific database of sensitivity readers, the Editors of Color “Database of Diverse Databases” is also a good resource for journalists committed to better representation.

In my next post, I’ll be turning back to healthcare content, and writing about how hospitals can do a better job with transparency in their “about” and “our story” content.

Photo by Giorgio Grani on Unsplash

**

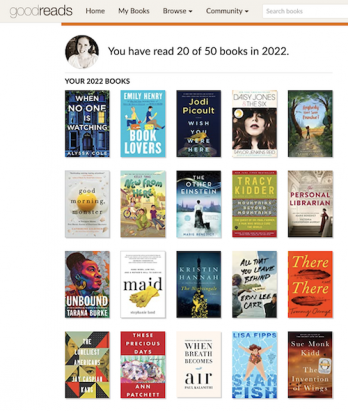

My 2022 Reading Challenge

I decided to do a Goodreads reading challenge of 50 books in 2022. I have friends who read 100+ books a year, so my challenge of about a book a week is rather modest. But . . . in case you need some reading recommendations for summer, my favorite books of the year so far:

I decided to do a Goodreads reading challenge of 50 books in 2022. I have friends who read 100+ books a year, so my challenge of about a book a week is rather modest. But . . . in case you need some reading recommendations for summer, my favorite books of the year so far:

- Favorite memoir: Unbound, by Tarana Burke

- Favorite adult fiction: The Personal Librarian, by Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray

- Favorite young adult fiction: Starfish, by Lisa Fipps

- Favorite audio book: Wish You Were Here, by Jodi Picoult, narrated by Marin Ireland

I’m currently listening to The Daughters of Erietown by Connie Schultz and reading The Mystery of Mrs. Christie, by Marie Benedict.

And [clears throat], if you’re looking for a nonfiction book to read, I wrote one! It’s about what it means to live a more honest life. Learn more.